Back in 2011, I started an internship at Kill Screen magazine. (They're an excellent magazine.) They treat games with the kind of respect I imagine the medium will receive in university classrooms fifty years from now--but they don't actually take themselves that seriously. It's a good thing. A really good thing.

The first piece I ever published was an analysis of the disturbing psycho-sexual terror game Haunting Ground. It's an amazing game. It's an awful game. It's exploitative and gross and weirdly beautiful and atmospheric and I swear the PS2 processor was loaded down mostly because it had to animate every polygon of the gorgeous blonde protagonist's chest.

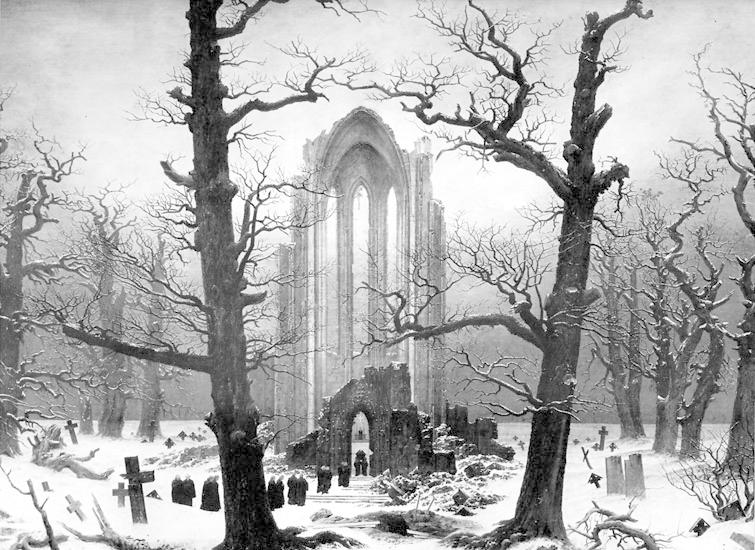

My essay has disappeared from the site in one of Kill Screen's many renovations. I'm reposting it here in case anyone is interested, along with the artwork that was commissioned for the piece. Also: this appeared as part of a short-lived but kind of cool exchange with Pitchfork? In case you didn't notice, I'm kind of proud of this piece.

A True Gothic

It’s a scene most of us have seen a hundred times over: a narrow hall fringed with old pillars, leering gargoyles, candles recently snuffed. Lightning flashes through a long row of windows, the wind batters against the intricately cut buttresses, and deep inside the castle is a beautiful young woman biting her lip, taking careful steps down the hall. Suddenly there’s a crack of thunder, and a looming shadow jumps from behind one of the many statues, bellowing threats: the girl screams and runs the other way. This is Haunting Ground.

Ann Radcliffe, a pioneer of the literary gothic romance, used terror as a mechanic of self discovery. It’s a concept our culture has dumped for cheap scares and thrills in cinema and games: our fears embody something deeper, perhaps darker than we’d like to admit. Terror is another word for self-discovery.

So much of modern horror—in gaming and cinema—is built upon a framework laid by the literary greats 300 years ago in the form of the gothic romance. Now when I write “gothic romance” I don’t mean Twilight-style romance or anything Tim Burton has ever created. I mean the actual literary tradition begun midway through the 18th century, which influenced Shelley’s Frankenstein, and later Poe’s macabre writing. These were the kinds of stories that basically all began with “It was a dark and stormy night” and featured a young attractive virgin running through a broken-down castle from a rapist or lecherous uncle. The genre as a whole was exploitative and weirdly voyeuristic. Once writers like Ann Radcliffe and Percy Bysshe Shelley took hold of the form, the public came to love it.

These tropes—dark, brooding castle; beautiful innocent virgins; paintings with moving eyes—were merely the trappings of the gothic, as laid down by Horace Walpole in The Castle of Otranto and perpetuated in Lewis’ The Monk and de Sade’s Justine. While these writers always cultivated a dark atmosphere of dread and suspense, the dark heart of the genre was rape.

Chances are you haven’t played Haunting Ground (Demento in Japan). Released in 2005, the game is a strange brew of gothic horror, psych0sexual torment, and dog training. Most notably, the game was cowritten by Noboru Sugimura, who penned the scripts for several Resident Evil titles and Clock Tower 3. The premise is cookie-cutter gothic: abandoned castle seasoned with basic run-and-hide gameplay, along with a set of perverted antagonists. This twisted drama epitomizes the traditional Gothic form of rampant lust and imperiled innocence. Haunting Ground’s gameplay is almost identical to that of Clock Tower, though the execution here is noticeably more refined, and more unified in tone, than its inspiration. However, most reviewers weren’t impressed. Released in the wake of Resident Evil 4, the game seemed tired and old-fashioned. Game Informer’s review called it “unquestionably less fun than doing one’s taxes” while Charles Herold of The New York Times wrote it contained “a mix of clever ideas and petty annoyances.” Yet while the environment and defenseless protagonist were lauded, nobody seemed to catch on to Haunting Ground’s blatant homage to the gothic form.

Fiona Belli, an innocent blonde amnesiac, wakes up naked, caged in the basement of a crumbling castle hidden away in an obscure patch of woods. She escapes wearing naught but a towel and, after donning a skirt that covers maybe a quarter of her thighs, sets out to explore her family’s inheritance. Little time passes before she runs into Debilitas, the groundskeeper, an addled brute who towers over Fiona. Having never progressed past a mental age of three, he is clearly unaware of the physical attractions that draw him to Fiona. He knows that he intensely wants to possess her, to hold her close like a doll. He stares at her for a moment, then throws his arms up monster-style and chases her across the grounds.

The young and helpless Fiona, much like Matthew Gregory Lewis’ Antonia in his 1896 novel The Monk, is “as helpless as a plaster statue demolished by an earthquake.” The Monk was essentially (for the time) a torture porn in literary form about a priest named Ambrosio and his eventual rape and murder of a young girl. Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote that the grotesquery was proof of a “low and vulgar taste,” while the critic David MacDonald has written that “The Monk was an eloquent evil … [a] poison for the multitude.”

The gothic form thrives upon the helplessness of its protagonist. Fiona can run, cower in a wardrobe, and in brief moments of valor, kick her assailants in the knee. Eventually she finds a friend in Hewie, a snowy-white dog who fights tooth and nail to save her, but she rarely ever “defeats” her assailants. The best she can hope for is to survive.

It's like Lassie. Or Shiloh. But more murdery.

Each of Haunting Ground’s four antagonists (that’s right—just four) are compelled by successively more warped desires. Fiona escapes Debilitas only to find herself drugged by the castle’s maid Daniella. In what may be the game’s most disturbing scene, Fiona wakes up to find Daniella first caressing her, then pressing hard on her belly, whispering, “I am not complete.” Fiona wisely flees, with the maid rushing after her brandishing a piece of razor-sharp glass. Just as Fiona delves deeper into the castle, her assailant’s desire becomes even more depraved. Daniella has only one desire: She wants to cut out Fiona’s womb and sew it into her own body.

This obviously wasn’t the kind of thing you’d see in print in the 18th century. Barrenness, however, is a driving force in Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, which laid the groundwork for every other gothic story. Sweet young Isabella finds herself pursued by the diabolical Manfred, who wants an heir because his wife Hippolyta is barren.

Haunting Ground’s characters are obsessed with the female form. Daniella screams at mirrors, intensely jealous of Fiona’s beauty. She accuses Fiona of wasting what she most desires: virginity. The symbolism in Daniella’s death is crudely ironic: cornered in a skylit room, Fiona assembles a set of mirrors and tricks Daniella into seeing her own reflection. The timbre of her screams cracks the glass and a long, jagged shard impales her through the navel, a cruel mockery of the procreative penetration she had desired.

Horror is too often concerned with cheap scares. Character growth is secondary. Writer William Godwin tried to capture “a series of adventures of flight and pursuit ... [with the] fugitive in perpetual apprehension [and] fearful alarm” in the gothic adventure. In Dead Space, excellent sound design and copious amounts of gore eviscerate all sense of self and safety, propelling the player into a perpetual adrenaline rush. Amnesia: The Dark Descent plays with lighting and perception to similar effect. Neither game is particularly concerned with its characters’ personal journeys, however. Isaac’s journey through Dead Space is mere escape and survival; in Amnesia, Daniel’s task is one of recovery rather than growth.

Fiona’s journey is one of coming into womanhood. She isn’t merely running from enemies: she is fleeing parts of herself she can’t bear to face head on. It is only when she is forced to turn and fight that she can make true progress. When Fiona defeats Debilitas’ disturbingly infantile lust, she is overcoming her fear of stasis, of remaining a child. When Daniella dies, Fiona puts to rest the jealous narcissism of her femininity. The last two—Ricardo and Lorenzo—embody her deeper fears: the former, of men, and the latter, her own desire.

The game’s final act is the most frenetic, the least coherent. Fiona finds herself pursued by the butler Ricardo who chases her through increasingly surreal rooms shouting, “Lend me your womb!” Where the literary Gothic antagonists’ lust was tempered with propriety, Ricardo has no scruples, no compunction. He hunts Fiona with ruthless efficiency, disemboweling her parents, shooting her dog, laying countless traps, all so he can rape her.He embodies everything Fiona hates about men: he is the murderer, the rapist, the pervert. His corpse is barely cold when Fiona meets her lecherous ancestor Lorenzo Belli. The threat at this point is unclear until Lorenzo miraculously grows young and handsome and gives pursuit. Fiona is finally confronted with her own desire: yes, her sexy grandpa is courting her in a really strange, aggressive way, and the truly disturbing thing is that she actually likes it. Her escape is cartoonish, almost parodic, with Lorenzo’s flaming corpse in literal “hot pursuit”, consumed by his own desire.

Fiona can never claim any sort of victory throughout the game. Most gothic stories have a protector, a character who steps forward to save the virgin in distress. While Fiona has her dog Hewie to defend her, the true protector in Haunting Ground is the player, who feeds her, hides her from her pursuers, and eventually sets her free.

Ann Radcliffe distinguished two kinds of fear. “Terror and horror are so far opposite,” she wrote, “that the first expands the soul, and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes, and nearly annihilates them.” In her dichotomy, terror is the sublime, the surreal. It’s Dante descending into hell. It’s James Sunderland leaving Silent Hill for good. It’s the admission of some great secret. Horror is opaque, all entrails and scares. In it, symbol and meaning are eschewed for ephemeral sensation. Horror is cheap.

In a game that provides unlockable dominatrix costumes, it’s difficult to define Fiona as anything more than a doll. If Haunting Ground were merely a novel, one could write it off as voyeuristic torture-porn. As a game, however, it concerns itself more with the player’s journey. As Fiona’s protector, the player guides her past every pitfall, much like Theodore from Otranto strove to preserve the life (and virtue) of Isabella. When one strips away the tawdry trappings of character and circumstance, the goal of the gothic form is to cut deep to the soul and uncover the lies and fears to which we cling. While Fiona’s screams are pre-recorded, ours are not. Haunting Ground draws us out of ourselves—to shout at the screen when Fiona trips, to grit our teeth when the villain falls, and to sigh with relief when she finally leaves the castle behind.

I recently published a narrative review with Kill Screen. You can read it here. If you liked this, get on my mailing list. I'll send out occasional updates on my projects. And leave a comment or share this nonsense.